Your entire career, from the National Park Service to OuterSpatial, has centered on mapping parks across the country. What drew you to the work?

It was a complete accident. Growing up in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains, I had long enjoyed outdoor activities like hiking, climbing, and camping. I never, however, really considered applying this love of the outdoors to my career. After graduating from the University of Tennessee with a degree in International Relations (obviously completely disconnected from the outdoors), my plan was to go to grad school for politics. I didn’t really have much to do over the summer though, so I took a Student Conservation Association internship with the National Park Service (NPS). I was looking for an opportunity to be closer to D.C. and I ended up doing trail maintenance and wildfire mitigation at a Civil War battlefield south of Richmond, Virginia.

As part of that work, I started to learn Geographic Information Systems (GIS) while mapping the trail system. It just so happened that the GIS Specialist at the National Battlefield had recently moved on to another position. This gave me the opportunity to start digging into GIS on my own. I never even intended to get into mapping and was actually planning to go to graduate school in D.C. This opportunity just kind of fell into my lap and I ran with it. I ramped up by taking a bunch of online classes, and I even ended up getting a graduate certificate in GIS. So, yeah, I wasn't planning on getting into mapping or working for the federal government at all.

What did you find when you started working at the National Park Service?

The people who work for the NPS are so passionate about their jobs and the special places they protect. People literally work for years, in many cases in seasonal or part-time furloughed positions, just to get their foot in the door! That doesn’t just happen at larger parks like the Yosemites and the Yellowstones; it happens at smaller parks too. Every park draws people who are passionate about the NPS mission. Being able to experience that kind of energy early on in my career was incredibly motivating, and it got me interested in all of the things I've been pushing forward since then.

I was also drawn to the number of stories to tell at NPS. A lot of people think of natural resources and recreation when they think of the NPS. In fact, only 63 of the 423 NPS units are National Parks. The other 360 units are National Battlefields, National Historical Parks, National Monuments, etc. So, NPS is in large part responsible for helping people understand and digest narratives of our country's history. I’ve always been more interested in using GIS to tell stories than I have been in the “science” aspect of GIS, and at NPS, there are endless stories to tell.

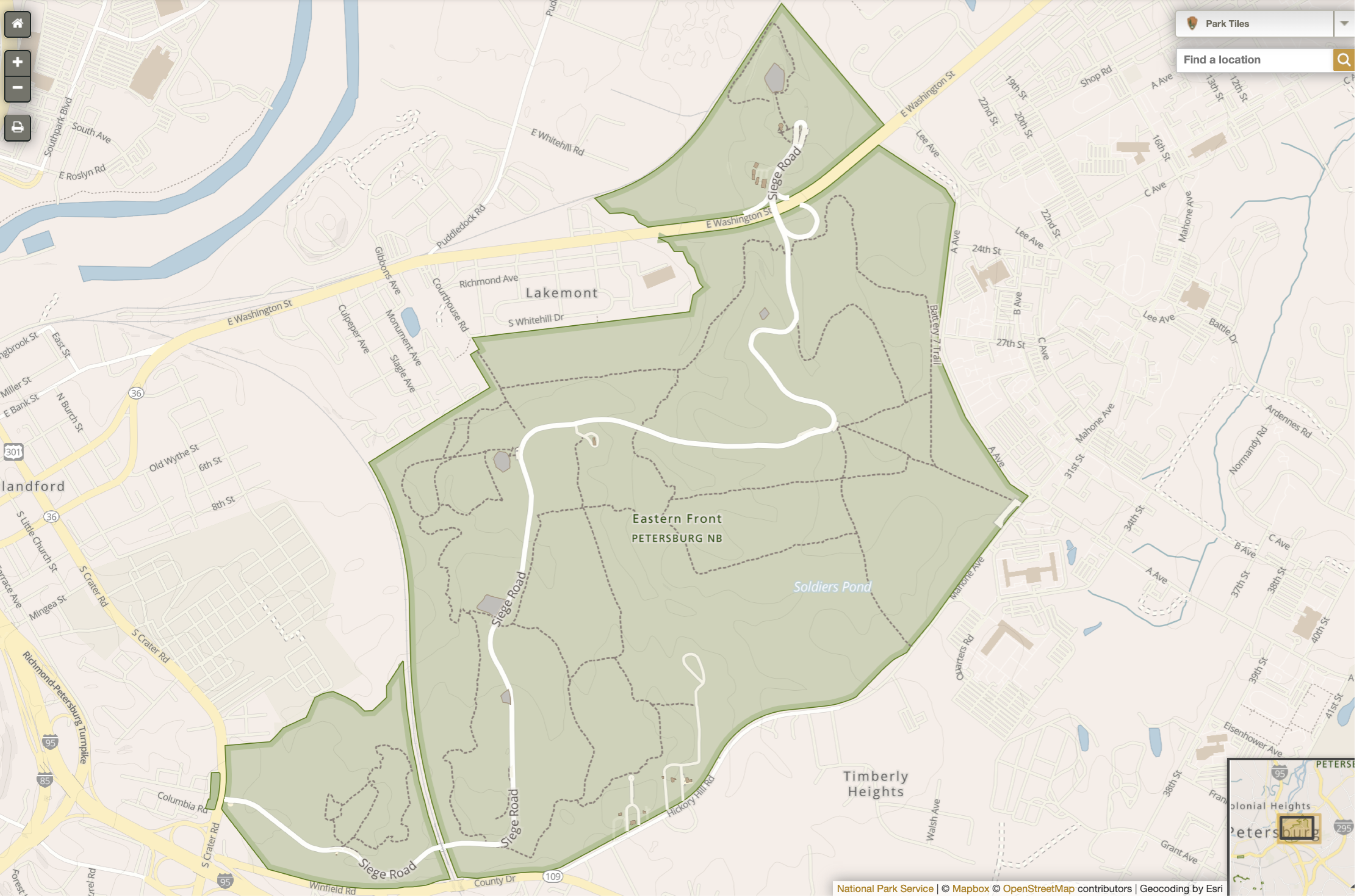

It didn't take long for me to get drawn in by this. My first taste of using GIS to tell a story while working at Petersburg National Battlefield in Virginia. I was working in the area where the 292-day siege of Petersburg occurred during the Civil War. Because the siege lasted for so long (the troops had to have something to do!), the city of Petersburg is surrounded by miles and miles of earthworks— many of which are completely overgrown with heavy forest. My job was to go out and mapping as many of these earthworks as possible, which often meant tramping through swamps and heavy vegetation (read: slow and painstaking work).

Once we had a solid understanding of the location of these earthworks, we were able to use the locations to georeference a series of 36” x 48” hand-drawn battle maps that were created by an NPS historian/cartographer back in the 1960’s. Using the georeferenced maps, we were then able to hand digitize the position of different troop positions and movements for a series of battles that occurred during the siege of Petersburg.

This was a transformative project because it opened my eyes to how GIS can be used to tell stories and this ultimately led to my career-long interest in creating visitor-facing experiences that engage and encourage people to get outside more. Ultimately, one of my driving principles is inclusivity, and that’s something that was really drilled into me during my time at the NPS. I share the service’s passion for getting more people outdoors and making outdoor experiences more accessible to all—especially for those who may not traditionally have had the means, the experience, or the skillset to get outside.

.png)

.png)

.jpg)